In the weeks running up to the rollout of the Covid-19 vaccine developed by the University of Oxford and pharma giant AstraZeneca, the UK’s NHS England gave it a codename. It was dubbed the ‘Talent vaccine’.1

The label is likely to have been in recognition of what Sarah Gilbert, professor of vaccinology at the university, describes as a “multinational effort”2 in which a global pool of talent came together to work towards a common goal.

But it is uncertain how likely it is that a similar initiative could be driven by talent in other regions of the world. Many countries have struggled to foster a strong base of local talent, either through a lack of guidance for students emerging from STEM subjects at university, or by falling prey to a brain drain effect as promising young scientists and technicians in low- to middle-income countries flock to markets that offer more lucrative opportunities.

Learn why the talent pool is an important part of the Biopharma Resilience Index

Though talent is vital to all industries, it is particularly so for pharma and biopharma given the sector’s complexity, making a shallow pool of local talent a real issue.

“Biopharmaceutical production is extremely specialized,” says Adrian van den Hoven, director general of Medicines for Europe. “You need specialist biochemists, engineers, even people with a lot of IT skills.”

So just how reliable is the biopharma talent pool, and can the industry ensure it has access to the people with the skills it so desperately needs long into the future?

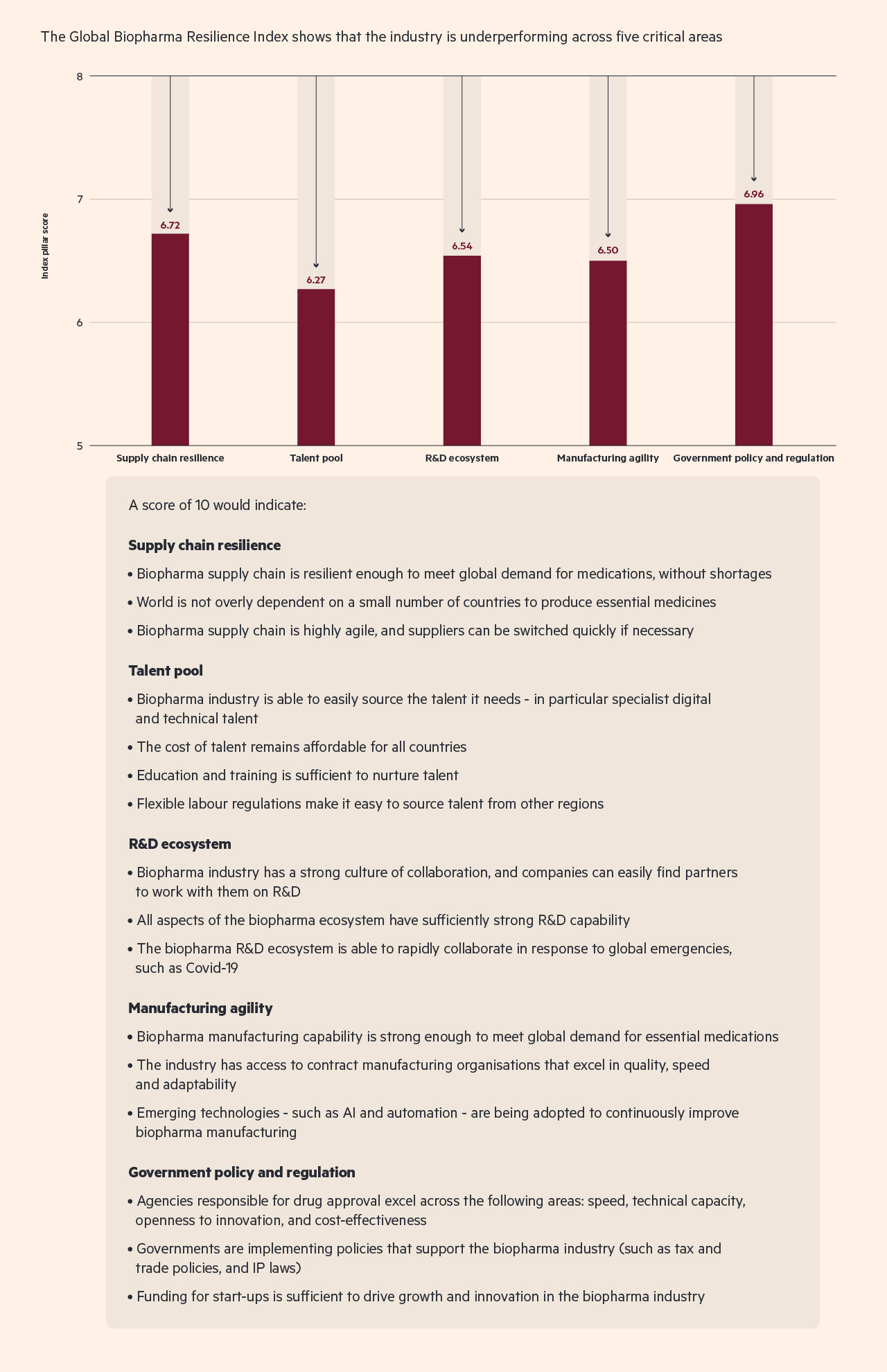

Cytiva’s Global Biopharma Resilience Index presents an unsettling picture of the anxieties surrounding pharma’s access to talent, which emerges in the index as the area where the industry is weakest (see chart 1).

Talent is now biopharma’s weakest link

Chart 1. The Global Biopharma Resilience Index reveals that access to talent is the area where the biopharma industry faces the greatest struggle

An expensive business

The idea that talent is freely available and easy to source only resonates with some of the survey respondents, and a quarter say the opposite: 25% say that the sourcing of talent in technology, manufacturing and R&D is a substantial or very substantial challenge.

Part of that challenge stems from just how expensive sourcing talent has become. More than 50% of executives and policymakers in the research say that the cost of talent has become a key issue in their country in recent years as expectations of benefits and remuneration have soared. The industry’s shift to more specific areas means greater demand for a limited supply of highly sought after skillsets, and local companies in lower-income countries face stiff competition from big multinational firms in high-income countries because of the kind of incentives they can offer.

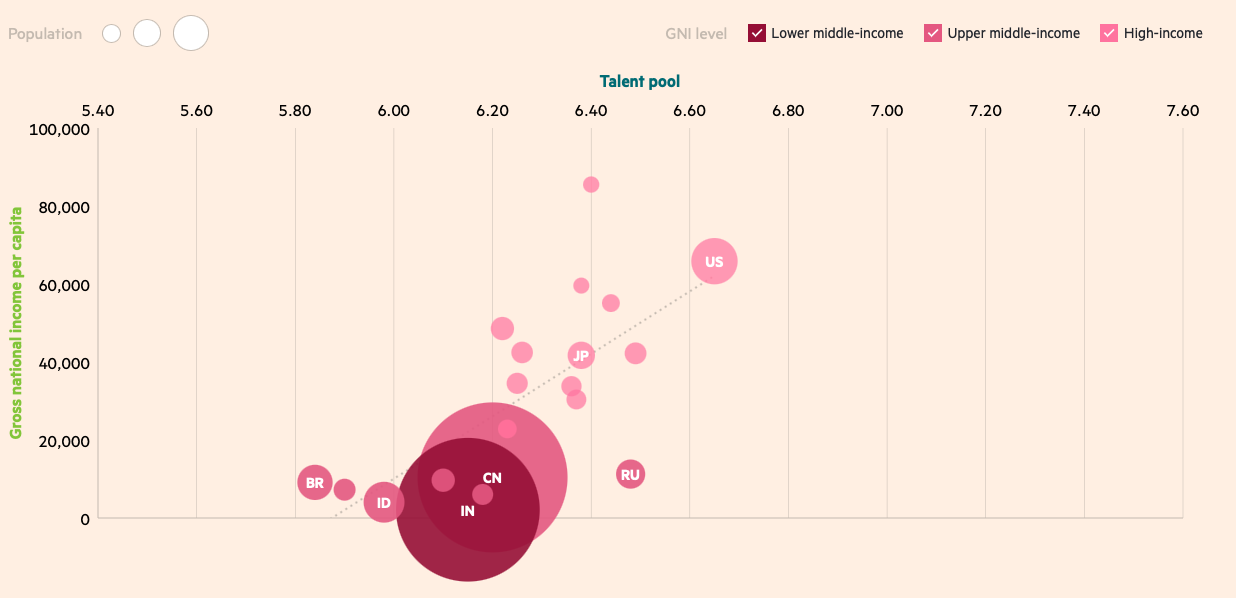

Japanese respondents are having the hardest time with talent costs, with an index score of 4.26 out of a possible 10. But the countries that lead the index overall — the US, the UK (both 4.55) and Switzerland (4.33) — do not fare much better (see chart 2).

Bureaucracy is another challenge. Rigid labor regulations appear to be a sticking point when it comes to accessing the right workers: just one in five respondents say that domestic policies around the use of foreign talent are “very flexible”. Respondents in Germany and South Africa reported the greatest challenges with regulation, scoring 6.36 and 6.31 in the index respectively.

This issue comes at a time when a rise in economic nationalism marks a shift away from a global order to one that puts domestic interests first. But unless countries can train the right people at home, cost and bureaucracy are going to become even more of a challenge.

Chart 2. Countries with a lower gross national income per capita are more likely to struggle to access talent

Home improvements

The way respondents feel about the quality of education and training in their own countries varies according to the level of expertise in question.

About three-quarters of respondents (74%) say they are confident in the quality of education and training for PhDs in the pharma sector. But only 69% say they are confident in workers with general technical skills, and 64% in engineers and workers with regulatory knowledge. It is a clear sign that the talent generated in academia for research and development roles is of a high caliber, but more could be done to bring other areas of industry up to standard.

More key insights from the BioPharma Resilience Index and expert panelists on the changing biopharma talent pool

Video: BioPharma Resilience Index: Talent