Could covid-19 be credited for spurring any positive change in the way we develop, approve, and commercialize new life-changing therapeutics? Biopharma leaders seem to think so; at least thanks to the unprecedented collaborations with government they relied on to bring vaccines to market in record time. Now, the industry appears optimistic that our pandemic-era learnings could modernize the way regulatory bodies measure efficacy and safety, helping them bring future therapies to market faster.

“The industry benchmark is that it generally used to take 10 years to bring a new product to the market,” explains Amanda Halford, Cytiva’s SVP of sales, service and commercial operations. The pandemic has changed that. The fast pace of vaccine development, she says, happened in part because the urgent risk to public health encouraged regulators to speed approvals by examining evidence concurrently rather than sequentially, but still based on their usual approval standards.

Building momentum around drug development

This acceleration happened in many countries. In the survey for the Cytiva Global Biopharma Resilience Index, conducted in late 2020 and early 2021, 70 per cent of respondents rated their national drug approval agencies ‘good’ or ‘very good’ on speed.

Instead of creating new rules, most drug approval agencies relied on authority already in place to provide temporary approval for products. Some could draw on straightforward rules. Singapore’s Health Sciences Authority, for instance, has a Pandemic Special Access Route for authorising new interventions during such events. Elsewhere, officials expanded on existing practice. In the past, emergency and temporary authorisation rules used for vaccines by the FDA in the US, the EMA in the EU and the UK’s MHRA had typically been applied only to very circumscribed cases, such as orphan drugs.

Many countries, however, lacked tools capable of such repurposing. “During the early parts of the pandemic,” says Jerome Kim, director-general of the International Vaccine Institute, “the pressure on regulatory agencies for diagnostics, repurposed drugs and vaccines was substantial, and countries scrambled to operationalise rapid but systematic review of submissions that might have contributed to suspicions that reviews were rushed and incomplete.”

Putting the lessons of the pandemic into practice

There are two lessons here for the future of regulation. First, faster regulatory decisions and faster access to drugs are possible without sacrificing safety. Second, the public wants clear rules for how and when this happens.

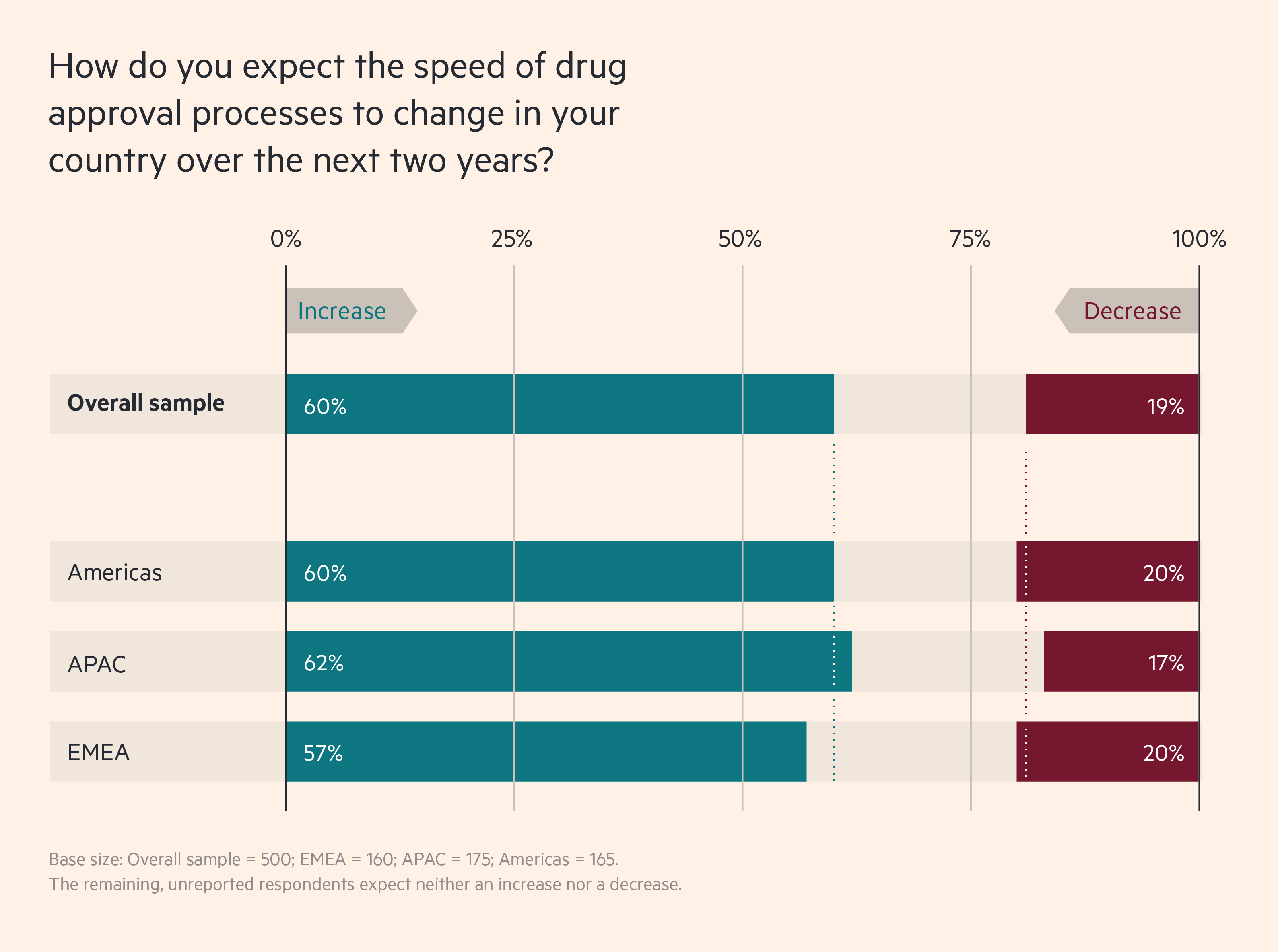

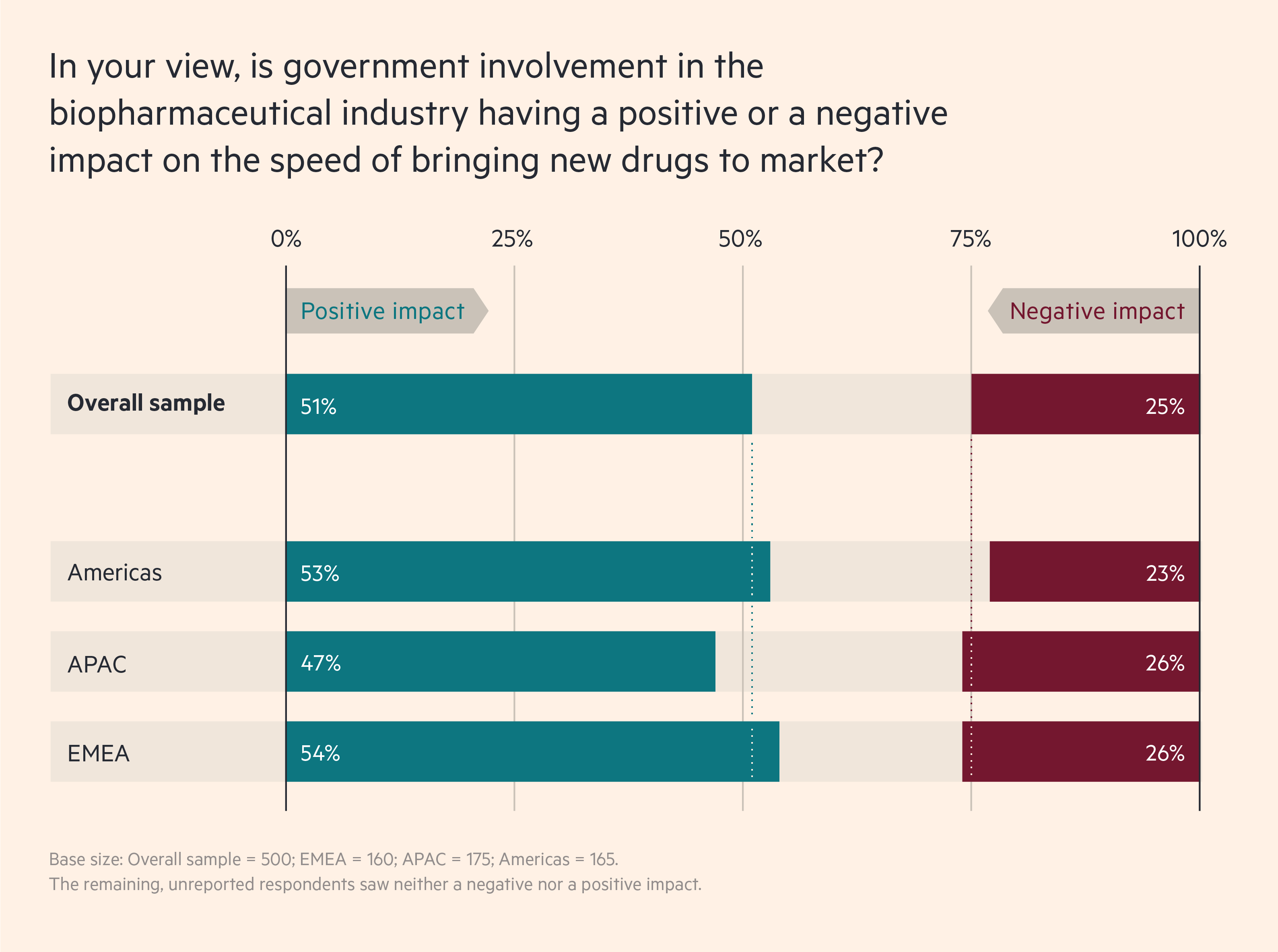

A majority of biopharma leaders expect this momentum towards faster regulatory action to continue. In a recent Cytiva survey of 500 biopharma executives in EMEA, APAC and the Americas, 60 per cent of respondents say they expect drug approval to become faster over the next two years, while just 19 per cent say it will slow down. And 51 per cent say that greater government involvement is already increasing the speed of bringing new drugs to market, while just 25 per cent say the opposite.

Biopharma leaders expect drug approvals to speed up

These numbers suggest that individual jurisdictions are changing at different rates. In Europe, for example, 63 per cent of UK respondents say that current government involvement is increasing the speed of bringing drugs to market, but in Germany that figure is only 43 per cent.

Collaboration accelerates the process

This acceleration is not about taking shortcuts in the assessment of safety and effectiveness. Instead, the aim is to reduce unnecessary delays.

In Abu Dhabi, for example, authorities looked at the steps needed to approve a new clinical trial, which resulted in the transformation of a multi-month process into one that takes just eight to 15 days. Those new regulations will continue to make it easier to initiate trials there.

Even more significant are the improvements in how clinical investigators and regulatory authorities share information. Jerome Kim recalls “a learning curve during the pandemic” as regulators moved towards the rolling submission of partial results during trials. “The FDA was able to make it happen in the US,” he says. “And other countries used a similar mechanism.”

This was part of a wider range of information-sharing that occurred during the pandemic. Amanda Halford explains that while contacts existed before the arrival of Covid-19, “the pandemic really accelerated that. You saw a lot more activity”. It began with cooperation on vaccine development, she notes, with innovations such as Operation Warp Speed in the US and the UK Vaccine Taskforce. This later expanded to sharing elsewhere in the vaccine value chain, “and then branched into supply chain issues such as scaling and manufacturing,” says Halford.

About half of biopharma leaders agree that government involvement is increasing the speed of bringing new drugs to market

Such extensive interaction has reshaped long-term relations for the better. “The conversations we are having, the level of collaboration we see across the industry and the way we are interacting with governments gives me a really positive view as we move forward,” says Martin Meeson, CEO of FUJIFILM Diosynth Biotechnologies. The challenge now, he says, is maintaining this momentum over the next five years.

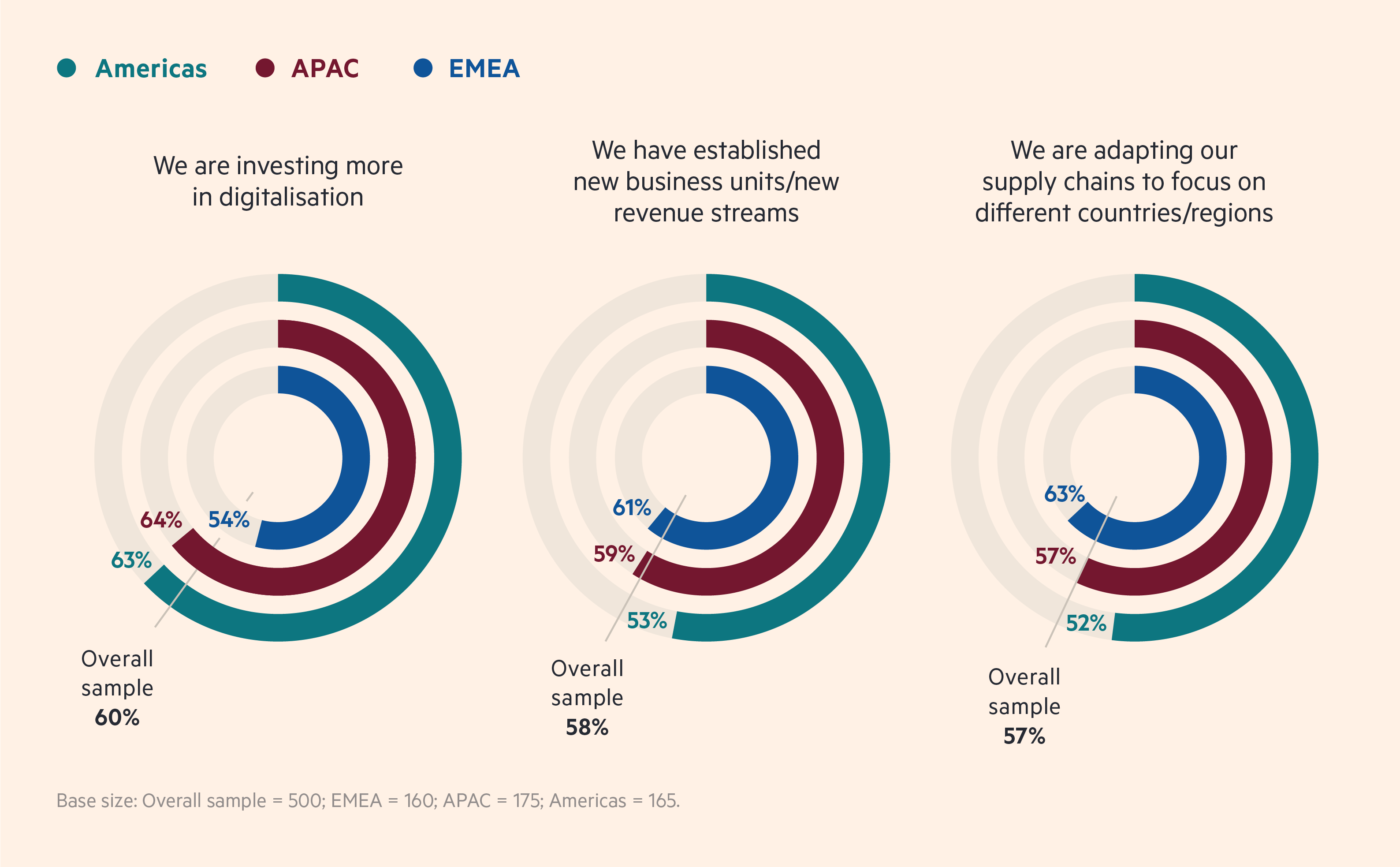

Increased government involvement is changing biopharma strategies

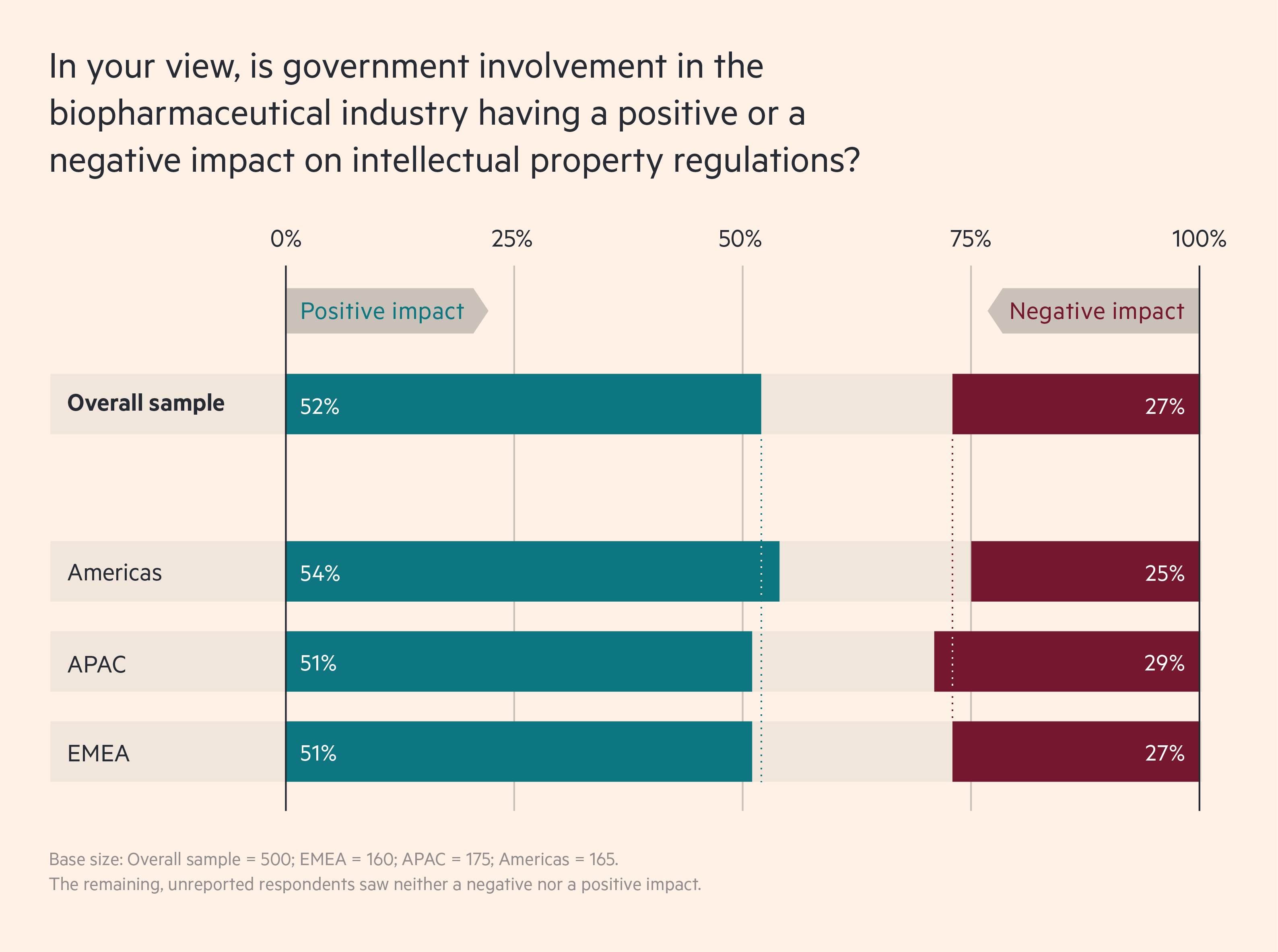

As these relationships deepen, extensive data sharing makes intellectual property (IP) rights more important. Here, 52 per cent of survey respondents agree that government involvement is having a positive impact, while only 27 per cent report a negative impact.

A closer look, though, shows that the effect of government involvement on IP will vary by country. In India, for example, which blocked exports of vaccines when Covid-19 peaked there, only 46 per cent say that government involvement has had a positive effect on IP, while 36 per cent say it has been negative. In China, which sought to expand its vaccine markets globally during the pandemic, the equivalent numbers are 58 per cent and 18 per cent.

Clear, robust IP protection rules are not simply a nice-to-have. Halford calls them “an important part of the framework for the whole [drug development] process.” Where they are absent, investment is inevitably less likely. This in turn can slow the development of, and access to, new treatments.

Now countries can build on the regulatory necessity

The new flexibility of drug approval rules and speed of regulatory action are part of an expansion of cooperation between governments and pharmaceutical companies. Fifty-four per cent of the survey respondents say that their senior leaders are collaborating more closely with government ministers/representatives. Only 15 per cent disagree.

What this looks like varies. It can involve — as with South Korea’s $2bn K Vaccine programme — extensive investment to help create domestic integrated research and development (R&D) and manufacturing capability.

Elsewhere, simply building on pandemic-driven regulatory progress is likely to have a dramatic effect. The Gulf states are a case in point. Before Covid-19, they lacked a strong pharmaceutical R&D or manufacturing base. But these countries adopted a simple policy goal: to be among the fastest to approve and gain access to new medical interventions against the pandemic. This, in turn, required an overhaul of regulations around R&D, IP and drug approval. The results speak for themselves. These countries were some of the first in the world to review, license and launch vaccines and later treatments.

Even where the pandemic did not bring major regulatory change, experts see the need for it. Guo Yunpei, president of the China Pharmaceutical Enterprises Association, for example, says that, even while China’s “system is constantly improving, we must simplify the drug approval process and keep up with world standards.”

Countries at different levels of development will take distinct paths, but each of them can benefit from the general lesson provided by the pandemic. “Both government and the industry feel a responsibility for taking the positive ways of working we developed through the pandemic and applying them to the development of other treatments,” says Meeson. “We now have a legacy of knowledge, which we need to put into practice.”